KUALA LUMPUR, Nov 11 — Once primarily used within China, social media and e-commerce platform Xiaohongshu has rapidly gained popularity among Chinese diaspora worldwide, including those residing in Malaysia and Singapore.

Nevertheless, Xiaohongshu is just one of many Chinese-developed platforms that have emerged from China’s internet ecosystem — a landscape shaped by the country’s rapid technological advancements and regulatory environment often dubbed the “Great Firewall”.

Reflecting the diversity within China’s internet ecosystem, several major platforms now dominate various sectors, from social media to e-commerce, even featuring search engines that mirror their Western counterparts.

Unlike the rest of the world, where platforms like Google and Facebook dominate, China has developed its own internet ecosystem, largely insulated from Western influence.

Search engines

Baidu

Founded in 2000 and often referred to as “China’s Google,” Baidu is China’s dominant search engine, with over 667 million monthly active users as of December 2023, offering services similar to its Western counterpart.

The name Baidu translates to “a hundred times,” inspired by an ancient Chinese poem where the poet (Xin Qiji) searches persistently through a crowd, symbolising the quest for the ideal.

A screengrab of Baidu’s homepage that shares similarities with Google.

Possessing the largest search market share in China, Baidu’s services are tailored to comply with local laws and government regulations, including active monitoring and filtering of content.

This includes censoring politically sensitive topics, explicit content, and information that contradicts state narratives.

As a result, users may see a different set of search results compared to international search engines, reflecting the government’s information control policies as Baidu prioritises state-approved content and sources.

Sogou

Founded roughly a decade after Baidu in 2010, Sogou — a subsidiary of Chinese technology conglomerate Tencent Holdings Ltd — is the second-largest search engine in China.

Their name literally means “search-dog” when translated from Chinese.

A screengrab of Sogou’s homepage that shares similarities with Google. A list of the ‘hottest’ and most searched topics appears on the search bar when prompted.

Sogou differentiates itself from Baidu by employing a different algorithm (comparable to Microsoft Bing) and taking a slightly more lenient approach to content filtering, which can result in variations in search results.

Social media

Founded in 2009 and often referred to as “China’s Twitter,” Weibo is a microblogging platform with over 598 million monthly active users as of December 2023, allowing users to post updates, share news, and engage with trending topics.

The name Weibo literally means “microblog” in Chinese.

A screengrab of state-run China Central Television (CCTV) Weibo’s account.

As China’s leading microblogging and news-sharing platform, Weibo operates under strict government regulations that enforce content censorship, with content heavily moderated.

One key difference between Weibo and its Western counterpart is the character limit per post — 2,000 for Weibo, compared to 280 for X, formerly known as Twitter.

With an average of 256 million daily active users as of December 2023, Weibo remains a vital space for social interaction, entertainment and marketing in the Chinese internet landscape.

WeChat (Weixin)

Released in 2011 and described as China’s “app for everything,” WeChat is a super-app that functions as an all-in-one platform for messaging, social networking, and mobile payments.

Widely used in both China and among Chinese communities worldwide (including Malaysia), WeChat embodies a digital ecosystem where social interactions and services converge seamlessly.

There are key differences in user activities depending on their location, as two separate versions of the application exist — localised as Weixin in China — designed to cater to different user needs and regulatory environments imposed by the Chinese government.

For instance, user activities on Weixin are analysed, tracked, and shared with Chinese authorities upon request as part of China’s mass surveillance network, including censorship of politically sensitive topics on Chinese-registered accounts.

Tailored for users outside of China, the international version lacks many advanced functionalities found in the Chinese version, such as WeChat Pay.

E-commerce

Taobao

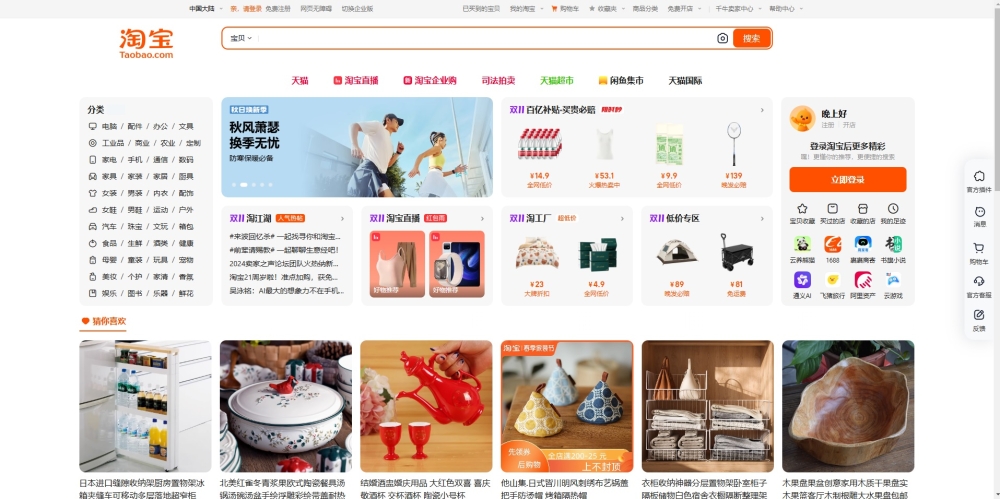

Launched in 2003, Taobao is one of China’s largest online shopping platforms, often described as “China’s eBay” as it facilitates consumer-to-consumer retail, allowing individuals and small businesses to set up their own shops and sell a wide range of products.

The name Taobao literally means “search for treasure” in Chinese.

A screengrab of Taobao (China)’s homepage which depicts the numerous categories of items for browsing on the left.

While eBay primarily focuses on auction-style listings and fixed-price sales, Taobao emphasises a more vibrant, decentralised marketplace with features like live streaming, social interaction and a broader range of sellers.

Its massive user base and integration of social media elements have made Taobao a cultural phenomenon and a go-to destination for online shoppers in Chinese-speaking regions outside of China, including Malaysia.

Content sharing

Douyin (TikTok)

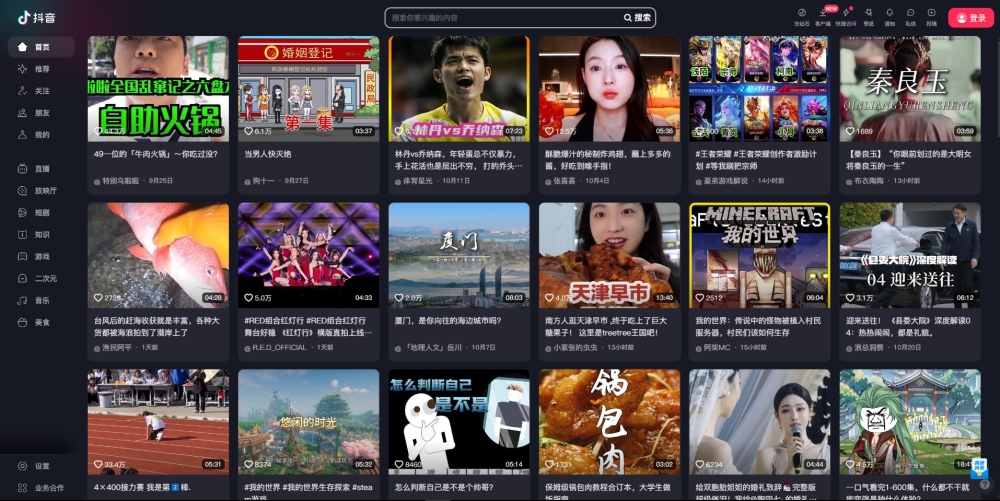

Launched in 2016, Douyin is the largest short-video platform in China, allowing users to create and share engaging, bite-sized videos akin to its international counterpart, TikTok.

The name Douyin translates to “shaking sound,” emphasising its focus on music and sound-centric short-form videos.

A screengrab of Douyin’s homepage.

Similar to WeChat, Douyin is specifically designed for the Chinese market and is available only in China, observing different regulations and content policies.

The platform offers a wider range of features, including advanced e-commerce integration, live streaming and social commerce tools. In contrast, TikTok, while also featuring some shopping capabilities, focuses more on entertainment and creativity.

Bilibili

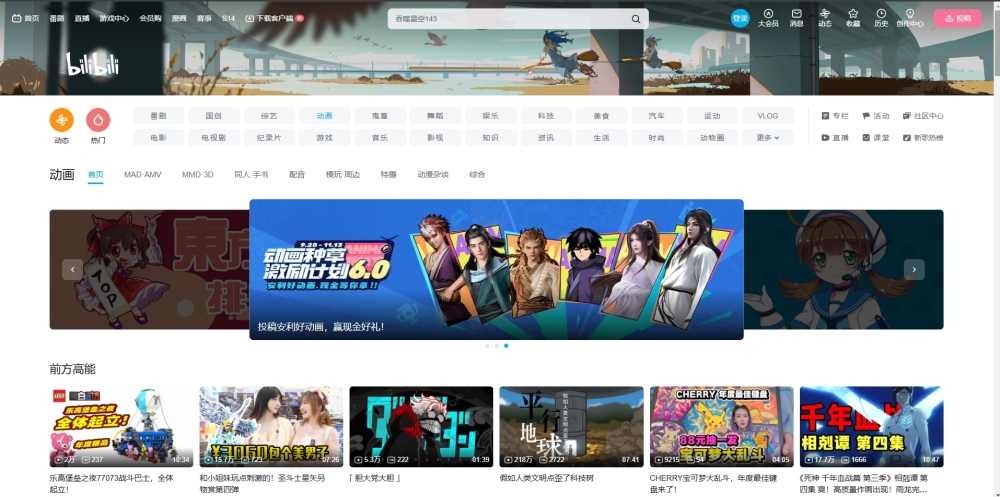

Launched in 2009 and often referred to as “China’s YouTube,” Bilibili is a major player in the Chinese video-sharing platform market with a strong focus on niche content like anime, gaming, and pop culture.

A screengrab of Bilibili’s homepage with the animation category selected.

Bilibili is known for its live streaming service and unique “bullet comments” or danmu system, which allows viewers to post real-time comments that appear as streams of scrolling subtitles overlaid on the screen.

Since its launch, Bilibili has built a dedicated user base, particularly among younger audiences and fans of niche subcultures.

It has since expanded to provide video content on automotive, travel, fashion, and maternity topics, setting it apart in the competitive Chinese online video and internet landscape.

In its 2023 Annual Report, Bilibili reported an average of 98 million Daily Active Users (DAUs) and 329 million Monthly Active Users (MAUs).

With its own unique platforms, China’s internet ecosystem is one of the most diverse and self-contained in the world, catering to the needs of domestic users while providing cultural touchpoints for Chinese-speaking communities abroad.