BBC News, Northamptonshire

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNetflix’s new drama Toxic Town revisits one of the UK’s biggest environmental scandals: the Corby toxic waste case.

The series tells the story of families fighting for justice after children in the Northamptonshire town were born with birth defects, believed to be caused by industrial pollution.

Corby’s steel and iron industry expanded rapidly in the 1930s with the construction of Stewarts and Lloyds steelworks.

By the 1970s, half the town worked in the mills, but when the steelworks closed in the 1980s, toxic waste from the demolition process was mishandled, leading to widespread contamination.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 2009, after a long legal battle, the High Court ruled Corby Borough Council was negligent in managing the waste.

Families affected won an undisclosed financial settlement in 2010, held in trust until the children turned 18.

Alongside the drama, a BBC Radio Northampton podcast series offers a deeper look into the real-life events, using original court transcripts and newly uncovered documents.

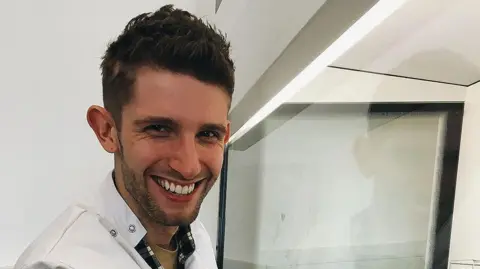

Hosted by George Taylor, 32, who was born with an upper limb defect linked to the case, the podcast features testimony and interviews with those directly impacted.

Here are some of the key voices behind the story.

‘The first person you are going to blame is yourself’

Kate Bradbrook/BBC

Kate Bradbrook/BBCGeorge Angus Taylor was born on 11 March 1992 to parents Fiona and Brian, in Corby.

Brian had worked at Stewart and Lloyds, a job that left him covered in dust and debris at the end of each shift.

Fiona, a former Boots No7 beauty consultant, vividly remembers George’s birth, an event that would change their lives forever.

Born “navy blue” as a result of pre-foetal circulation issues, he was immediately ventilated and placed in intensive care.

It was then Fiona noticed something unusual.

“I remember just seeing his little hand; his pinkie ring finger and middle finger,” she says.

“It was like a fist; you know how babies make a fist? Then his index finger; his thumb was sticking out.

“I just kept thinking, ‘He’s here because of me,’ and you just look for blame. You look, and the first person you are going to blame is yourself.”

Tim Wheeler/BBC

Tim Wheeler/BBCAt 14, doctors discovered a tumour in George’s hand so large that amputation became a real possibility.

The surgery, experimental at the time, was gruelling. “When I woke up, I was so full of morphine,” he remembers.

“They said it was like climbing Everest with no practice – my body just shut down.”

The experience, particularly the smell, left lasting memories. “They burn flesh as they [operate]: very quiet sizzling, like sausages in a pan. And that’s the smell that still comes to you from time to time.”

Despite everything, George was determined to move forward. “The first time I saw my hand, I wasn’t shocked. I wasn’t sad. It was better than before.”

But George was not alone. Other children in Corby were born with similar conditions.

‘Did I do this?’

Supplied

SuppliedLisa Atkinson was a security guard at the Corby steel mills, where her duties involved outside patrols, checking parking permits, and often having to move dust that had settled over everything.

On 27 June 1989, she gave birth to her daughter, Simone, at Kettering General Hospital.

Simone was born with three fingers on each hand.

Doctors reassured Lisa, saying the only thing she would not be able to do was play the piano.

Just as Fiona Taylor did with George, Lisa initially questioned whether she was responsible for her daughter’s condition.

“There was probably part of me that sat there and went, ‘What did I do? Did I do this?'” she says.

“Because I’ve had a couple of miscarriages before Simone… I always thought maybe I was lucky; maybe I was given Simone… but she wasn’t quite perfect. But I was lucky to have had that baby and not the two previous ones.”

Supplied

SuppliedDespite her initial self-doubt, Lisa “knew” she had done nothing wrong, as she had neither drunk nor smoked during pregnancy.

She recalls the lack of follow-up care or investigation into her daughter’s condition.

“You’re let out into the world with a child that’s a little bit different,” she says.

“But there was nowhere to go. There was no follow-up or anything, no ‘We’re going to look into it.’ So you just deal with it. And you did, because you had to.”

Lisa quickly adjusted to life with Simone’s condition, saying: “It shocked other people more than it shocked me. I got used to it really, really quickly.”

Winning the subsequent legal case against the borough council brought with it overwhelming attention.

“I’m not famous, but I feel like that’s how famous people must feel… It was crazy.”

Growing up, Simone, now 35, faced relentless bullying.

“I had a great family and friends… but [school] was hard. I wasn’t a very confident child, and I was an easy target,” she remembers.

Simone coped by using humour. She would joke that her mum had chopped off her fingers or that she was part alien, turning her differences into something entertaining.

“It was a bit of a front, because if I make a joke about myself, nobody else can. Just accept that’s who you are; it’s not going to change.”

At 18, she was offered surgery to reshape her hands, but declined.

“They admitted they didn’t really know if it would help. By then, I’d adapted. I live with daily pain, but I didn’t want to risk making things worse.”

Meeting her now-husband, she initially hid her hands, subtly positioning herself to avoid detection.

Eventually, she told him – through a long message and sending him a link to the 2020 Horizon documentary about the case.

His response? “It’s really not a big deal.”

Today, she is grateful for the legal battle her family fought. “It set me up for life,” she says.

“I was able to start my own life, and I went to university. I’ve got my own house and my daughter had the best start in life.”

‘It felt like we were an inconvenience’

University of Northampton

University of NorthamptonLewis Waterfield was born in 1994 with deformities to both hands.

His father worked near the contaminated site as a roofer, and his pregnant mother often visited him there.

“My dad noticed something wasn’t right straight away,” Lewis recalls.

As a child, he endured disruptive hospital stays, including an unsuccessful attempt to graft a toe on to his hand to create a functioning finger.

“I’ve had extensive surgery, but there are limits to what can be done.”

During the legal battle, Lewis’s parents fought to prove a link between industrial pollution and birth defects.

“The council, I remember, was dismissive. It felt like we were an inconvenience to them.”

Now a senior lecturer in public health at the University of Northampton, Lewis acknowledges how his experiences shaped him.

“Every now and then, someone asks about my hands, and it takes me right back.” he says.

“But I don’t mind. It’s part of who I am.”

University of Northampton

University of NorthamptonCorby Borough Council ceased to exist in 2021 when it merged with other authorities to become North Northamptonshire Council.

In 2010, its then chief executive, Chris Mallender, issued a formal apology over the scandal.

“The council extends its deepest sympathy to the children and their families,” it said.

“Although I accept that money cannot properly compensate these young people for their disabilities and for all that they’ve suffered to date and their problems in the future, the council sincerely hopes that this apology, coupled with today’s agreement, will mean they can now put their legal battle behind them and proceed with their lives with a greater degree of financial certainty.”

BBC Radio Northampton’s eight-part documentary series In Detail: The Toxic Waste Scandal, is for download from BBC Sounds.