Cleveland had a connectivity crisis. Detroit too.

When the Covid-19 pandemic shuttered schools in 2020, students were suddenly thrust into a world of online classes at home. That wasn’t an easy switch, even for affluent students with their own computers and internet service at home.

But in high-poverty cities like Cleveland and Detroit, it was a full blown crisis with thousands of students lacking computers and any internet access.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Nearly half of families in the two cities had no broadband internet service — strong connections to home devices such as computers, not just on mobile phones — making them the worst-connected cities in the U.S. in one ranking. Other high-poverty cities, including Baltimore, Memphis and Newark, were close behind.

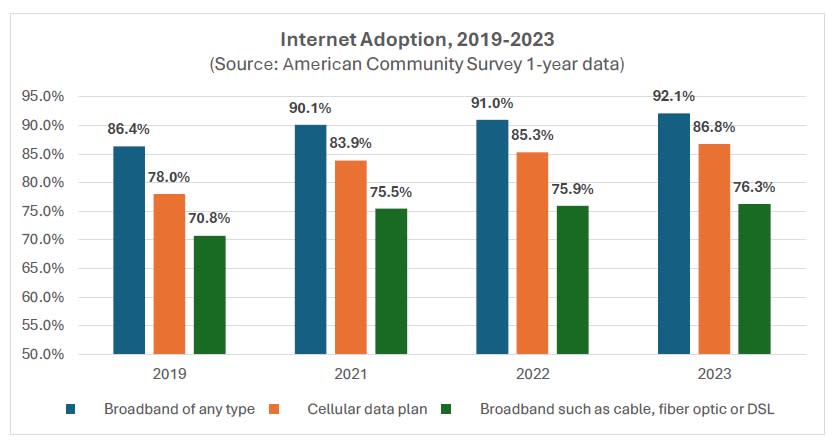

Today, a little more than five years since the pandemic shut schools down, the crisis isn’t as immediate — schools are open after all — but structural issues remain. Connectivity rates have improved nationally from about 71% of homes having broadband service in 2019 to more than 76% in 2023, still far from everyone.

”The pandemic highlighted for federal and state government that we have an issue,” said Charlotte Bewersdorff, vice president of community engagement of the Merit Network, a partnership between Michigan’s universities that has worked to improve internet access even before Covid hit. “A lot of our work prior to that was trying to convince people that there was an issue. The pandemic made it undeniable.”

Gains were greater in the cities that had the greatest need. Cleveland and Detroit each went from having nearly half of homes without broadband down to a third, according to U.S. Census data.

Internet connectivity has improved nationally since 2019, both in broadband home connections and through mobile phones, though most happened at the start of the pandemic and has since slowed. (Benton Institute for Broadband and Society)

But now those gains are threatened.

Most connectivity improvements were made in 2020 and 2021 — at the height of the pandemic — but have since stalled. A key federal emergency effort to help families be online by paying part of their monthly bill has ended. Some long-term improvements using Covid relief money are planned but have been slow to start.

The programs are now in limbo as Congress has changed its focus and President Donald Trump ordered a pause in January on many infrastructure investments, including internet efforts with funding set aside in pandemic relief bills but hadn’t started work yet. There’s also controversy over satellite-based internet potentially becoming eligible for federal subsidies, which would benefit Elon Musk, the billionaire owner of the Starlink satellite company and close advisor of Trump.

“The initial agility and efforts to help everybody get connected lost steam as other programs and other problems emerged,” said Johannes Bauer, the chief economist of the Federal Communications Commission in 2023 and 2024. “There’s a risk that the gains that were made very early on are actually diminishing over time, and new programs haven’t yet filled that gap.”

Providing internet access for all has long been a goal of digital equity advocates, though it has never been easy to achieve. There’s an infrastructure challenge: Homes need a service to connect to, which isn’t always the case. Families need to be able to afford it. They need computers to use it. And they need to know how,

All of these were hurdles when the pandemic hit, particularly for low-income areas.

Schools and nonprofits scrambled to hand out laptops and mobile hotspots. Some parked buses with wifi service in neighborhoods. Learning pods sprouted at churches, community centers or clubs like the Y.M.C.A. or Boys and Girls Clubs, where plexiglass dividers separated properly-spaced desks for students to take classes on just-acquired laptops.Club staff came to work every day while school staff stayed home.

Suddenly, “digital equity” was a focus of legislators and the federal government, which soon offered billions in grants to help families pay internet bills and to add fiber optic lines and other internet infrastructure to disconnected areas.

States created departments to oversee broadband investment, while the federal government created detailed maps of internet availability block by block to help target aid. All 50 states created digital equity plans to compete for grants and help connect and educate underserved groups. Many states have also submitted plans and won early approval for plans to connect rural areas.

But there are worries. The Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP), created by Congress during the pandemic, gave a peak of 23 million homes $30 a month to reduce their internet bills, but Congress let the funding expire in 2024. And billions set aside for both rural and urban

infrastructure and for internet education is also uncertain while the Trump administration picks new leaders to oversee grants and Republicans in Congress seek to change rules guiding them.

Beyond just pausing infrastructure projects overall, Trump’s orders to half spending on “Diversity, Equity and Inclusion” in all parts of government threatens efforts to connect and train families under the Digital Equity Act, another pandemic response.

Cleveland and Detroit highlight the mixed impact of the pandemic on connectivity. The two cities remain the worst-connected cities in the U.S., but they have also seen the greatest improvements in connectivity rates the last few years, according to census data analysis by digital equity advocacy group Connect Your Community.

Those cities each slashed the percentage of families with no broadband service in half – from around 46% in each city in 2019 to about 23% today, according to Connect Your Community and 2023 data from the census.

“It has gotten completely better,” said Gloria Jones, director of the Boys and Girls Club near the King Kennedy public housing apartments in Cleveland. The club’s pandemic learning pod once drew more than 30 students every day to do online lessons.

“When we first started out, there were kids that didn’t have any access,” she said. “That’s why we had to set up. Or their internet was running slow. If you’ve got three kids in the house and y’all are trying to get on the same internet, it slows it down.”

Today, students mostly use the club WiFi only for an online tutoring program the club provides. She said families seem to have found low-cost service, even if not at ideal bandwidth, often from cell phone companies.

Students work on an online tutoring program at a Boys and Girls Club in Cleveland early this month. When Cleveland’s internet crisis was at its peak during the pandemic, more than 30 students did online classwork here every day. (Patrick O’Donnell)

The landscape has changed so much in Cleveland that the Cleveland Municipal School District, which had to scramble to buy its 35,000 students laptops and digital hotspots for the 2020-21 school year, has cut its hotspot program way back. The district gave hotspots to 12,000 students — about a third of the district’s enrollment — in 2023, but cut that in half to 6,000 by last spring because students weren’t using them for months at a time.

“We turned them off,” Curtis Timmons, the district’s Chief Information Officer, said as budget cuts were announced last spring. “If you don’t use a hotspot that tells us something – that’s a waste of our money.”

The need for hotspots will reduce further with the district now offering students free internet service from Digital C, a unique non-profit the district has partnered with since 2020 that aims to provide low-cost broadband using wireless technology. It’s a plan that has caught the attention of connectivity experts, who could not point to another new, public—private partnership like it.

Using private donations and federal pandemic relief dollars from the city, Digital C has nearly finished building a network across the city so it can offer 100 mbs service for $18 a month.

The school district, city and county housing authority all allowed the company to put transmission towers on school buildings to keep costs down. About 1,300 families with students in the district now use it for free internet.

Nichelle Montoney, guardian of two boys, 13 and 10, in the Cleveland school district said free service from Digital C makes a big difference for her. She kept her internet service after ACP ended, but her $50 monthly bill from the cable company was hard to pay.

“I didn’t have a choice,” she said. “That bill barely got paid…when you have to choose between paying the gas bill and the light bill. You pay just under the minimum requirement to put it towards the cable bill, so you can try to get just another 30 days and hope that it stays on. It was a struggle.”

Other residents are still slow to sign on. The service has about 3,600 subscribers, out of about 90,000 households in its service area. Digital C still aims to eventually have 22,500 homes subscribed, nearly half of those without internet service now.

Detroit also had major efforts to connect people. A partnership with the city, United Way and the Rocket Mortgage company, which is based in Detroit, rallied as “Connect 313” — named after the city’s area code — to provide training and low cost laptops and hotspots to people. The city also used pandemic relief money to create 30 “tech hubs” in libraries, community centers and non-profits around the city that remain open today for residents to access the internet.

A flyer for Detroit’s 2023 drive to have students sign up for federal money to help pay internet bills under the Affordable Connectivity Program. (Detroit Department of Innovation and Technology)

It is also trying to add fiber optic cable to one neighborhood to improve connectivity there as a pilot project, but the plan has had trouble finding money and contractors.

And it boosted its connectivity numbers with a major drive with television and radio commercials in late 2023 to sign up more residents for ACP internet benefits. Detroit and Cleveland were leading cities for internet subscribers using ACP, but many more eligible families never took advantage.

“It was kind of like a last chance effort to show them (federal officials) this is a really big need, in the community,” said Jenninfer Onwenu, a senior advisor in Detroit’s Digital Equity and Inclusion office. “This is something that people were not aware of that they could be benefiting from. Imagine how many lives we could change by keeping this program in place. Unfortunately, that did not work out.”

Republicans opposed extending ACP as a “wasteful” part of a Democratic “spending spree” because it was costing billions and some estimates showed that only about 20 percent of recipients added internet service because of ACP,while most just enjoyed a discount on service they already paid for.

Digital equity advocates worry, though, that new census data available this fall will show that families had to drop their service without ACP’s help. Some loss is likely, with major communications companies reporting subscriber losses last year they attribute to ACP’s end. Comcast, the nation’s largest internet provider, reported losing 87,000 subscribers in one quarter last year mainly because ACP expired.

John Horrigan of the Benton Institute for Broadband and Society, a Chicago-area non-profit, estimates that about 11.5 million households are vulnerable to losing access and that ACP bill reductions kept 8.8 percent of households nationally online.

“The digital divide is not about being ‘on’ or ‘off’ the network,” Horrigan said. That framing makes it seem as if once a household is on, it has permanently hurdled the barrier that separates disconnection from connection…There is more uncertainty and churn in broadband at the low-income end of the market than some may appreciate.”

At-risk families like these are who Digital C in Cleveland is hoping to connect, though Detroit and other cities don’t have a similar backstop.

“Their safety net is being cut,” said Digital C’s Edmonds. “In the absence of that funding, locally, we have an answer.”

Republicans in Congress are also opposing grants to states and communities under the pandemic-passed Digital Equity Act and the Broadband Equity Access and Deployment Program (BEAD) for their focus on serving ethnic and racial minorities, both in who the projects will serve and who is hired to work on them. Such a race-based program is unconstitutional, Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas has charged.

U.S. House members have also raised concerns about the BEAD infrastructure program, which has states with plans ready to begin, but are now on hold. A House subcommittee blasted that program in a March hearing it named “Fixing Biden’s Broadband Blunder.”

”The Biden-Harris Administration saddled the BEAD program with regulations unrelated to broadband to appease left-wing interest groups,” said Rep. Richard Hudson, a North Carolina Republican, the sub committee’s chairman. “These included technology preferences, burdensome labor rules, and climate change requirements, to name a few.

He and others want to ditch BEAD’s old preference for fiber optic lines for a “technology-neutral” approach that would allow the allotted $42 billion to also cover satellite projects.

Democrat Doris Matui of California immediately objected to what she called “sabotage” of projects ready to begin.

“Republicans claim they’re just being technology neutral,” the ranking Democrat on the subcommittee said. “But can we trust this when the Trump administration has given Elon Musk nearly unfettered authority to further his business interests by taking over government contracts and dismantling agencies regulating his companies?”