States took on the mantle of combating climate change during the first Trump administration. Now they need to redouble the work during the second.

That’s the message that Caroline Spears, executive director of Climate Cabinet, has for state lawmakers following Trump’s victory on Tuesday.

As an advocacy organization that helps state and local leaders “run, win, and legislate on climate change,” Climate Cabinet supported more than 170 candidates in Tuesday’s election. As of midday Wednesday, when Spears spoke to Canary Media, she was feeling cautiously optimistic about the races her group had focused on: “About a third of them we won, about a third of them we lost, and about a third of them are still too close to call.”

Getting climate-committed candidates into state offices can make the difference between a state enacting or preserving climate policies and it blocking or rolling back such policies, she said. For example, the 2022 midterms saw Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Minnesota secure Democratic “trifectas” — control of the governor’s office and both houses of the state legislature — leading to significant climate legislation being passed and signed into law in those states.

States have “always been key to climate policy,” Spears said, and now, with a Trump administration expected to attempt to unravel the Biden administration’s climate policies and unleash fossil fuels, it’s “up to state leaders to hold the line.”

How states can keep the energy transition moving

State lawmakers and regulators have the ability to order local utilities to shut down or reduce emissions from fossil-fueled power plants and expand the share of electricity they generate from zero-carbon resources like wind, solar, geothermal, and nuclear power.

States can also require large polluters — like fossil-gas utilities — to reduce the amount of greenhouse gas they spew into the air and set emissions and energy-efficiency requirements for buildings. At present, states have the authority to adopt vehicle emissions standards that are more strict than those set by the federal government — although Trump sought to rescind that authority during his first term and may attempt to do so again.

States also play a key role in distributing funds from the federal Inflation Reduction Act and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act — at least while the full laws remain on the books.

During the first Trump administration, “we saw states really taking charge,” said Jeff Deyette, deputy director of clean energy at the Union of Concerned Scientists, an advocacy group. “I think that momentum has been maintained over the past eight years. This could be another boost to continue to push those state leaders … to protect what they have.”

There’s a lot to protect. The roster of states with aggressive decarbonization targets has expanded under the Biden administration: Colorado, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Washington state all adopted strong emissions goals in 2021 or 2022.

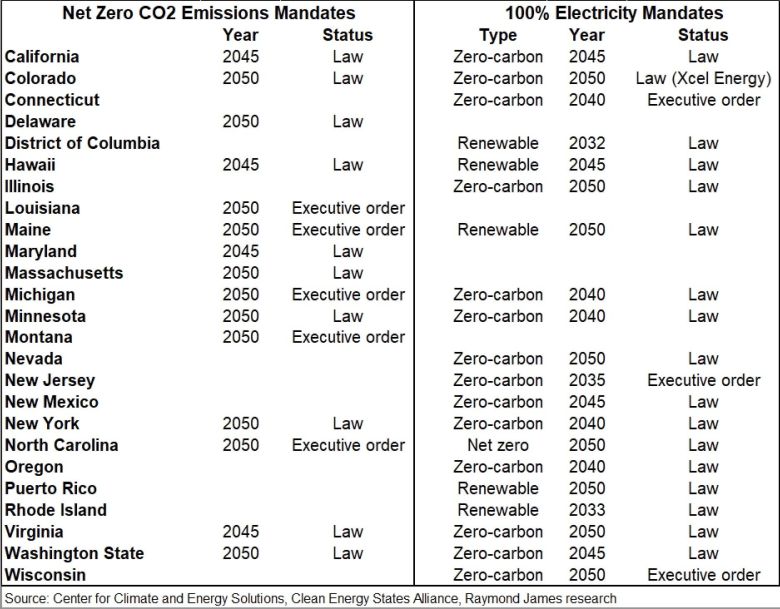

All told, 25 states and Washington, D.C., have now instituted some form of target for achieving either economywide net-zero carbon emissions, 100 percent renewable or carbon-free electricity, or both. This chart, compiled in mid-2024, includes all of these states except Vermont, which in June 2024 passed a law mandating 100 percent renewable energy by 2035 for all utilities and by 2030 for its largest utility, Green Mountain Power.

How the 2024 election changed the state policy landscape

Clean energy and climate policies aren’t necessarily partisan issues, said Heather O’Neill, CEO of trade group Advanced Energy United. “We see the potential for broad agreement in states of all political stripes and persuasions,” as utilities grapple with rising electricity demand from data centers, factories, electric vehicles, and broader economic growth. “Advanced energy technologies are a low-cost solution to all of these challenges,” she said.

She cited the example of Texas, a red state that’s deployed more wind and utility-scale solar power than any other state and is set to pass California for having the most grid-connected batteries by year’s end. Those resources are “working to keep the grid reliable,” O’Neill said, as shown by the role that solar and batteries played in averting grid emergencies this summer.

But to date, Democratic control has been a prerequisite for passing aggressive climate or clean-energy legislation in almost every state that has done so. The exception is North Carolina, where the GOP-controlled legislature passed a law in 2021 mandating that Duke Energy, the state’s biggest utility, cut carbon emissions 70 percent below 2005 levels by 2030 and reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

Heading into the election, 17 states had Democratic trifectas and 23 states had Republican trifectas. No state appears to be on a path to form a new Democratic trifecta as a result of the election; rather, Democrats have lost full control in Michigan and might do the same in Minnesota.

“We were in defense mode in Minnesota and Michigan,” Spears said.

In Michigan, Republicans gained a majority in the state House of Representatives, while Democrats retained a majority in the state Senate and Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer still has two more years in her term. That means the state is likely to protect a slate of climate bills passed in 2023, including a mandate for the state’s two big utilities to reach 80 percent carbon-free electricity by 2035 and 100 percent by 2040.

The situation in Minnesota is still up in the air. As of Thursday evening, the state House was evenly split between parties, with two remaining races set for automatic recounts due to razor-thin vote differences. But Democrats retained their majority in the state Senate, and Democratic Gov. Tim Walz remains in office. Even if Republicans end up narrowly controlling the House, they likely won’t be able to overturn the state’s 2023 law requiring power utilities to use 100 percent clean electricity by 2040 or a slate of bills creating incentives for electric vehicles and converting homes and buildings to more efficient electric heating.

In Pennsylvania, a state where Democrats were thought to have a chance at forming a new trifecta, Republicans appear set to retain their majority in the state Senate. Democrats could maintain their thin majority in the state House, but the outcome depends on three races that have yet to be called. Democratic Gov. Josh Shapiro has proposed a carbon cap-and-invest program that would collect funds from power plants and use them to lower electric bills and support clean energy projects, but it’s unlikely to pass without Democratic majorities in both houses of the state legislature.

The clearest victories for candidates backed by Climate Cabinet in this election cycle have been in North Carolina and Wisconsin, Spears said — though their wins did not give Democrats legislative majorities.

In Wisconsin, gains by Democrats eliminated a Republican supermajority in the Senate, giving Democratic Gov. Tony Evers the ability to veto legislation out of line with his climate agenda, she said.

In North Carolina, Democrat Josh Stein, the state attorney general who won his race to succeed Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper, will, “unlike his predecessor, have a veto pen that works, because we broke the supermajority” in the state House, she said. Republicans used that supermajority to override Cooper’s veto of a bill that weakened the efficiency requirements in building codes for new homes in the state.

Voters also chalked up some climate wins with state ballot measures in Tuesday’s election. Californians passed a $10 billion climate bond that included $850 million for clean energy infrastructure — the largest of a number of local and state climate and environmental bonds passed across the country, which together will invest $18 billion. And Washington state voters rejected a ballot initiative that would have rolled back its landmark 2021 climate law.

Turning pledges into action

For the states that have already managed to get climate goals on the books, living up to those commitments is now even more urgent.

State climate mandates must be followed up with continuous action from regulators, utilities, and private-sector actors to translate into actual emissions reductions. Right now, it’s far from clear that the states with decarbonization goals are on track to achieve their targets.

A 2023 report from the Environmental Defense Fund found that the 24 states with ambitious targets were on track to cut emissions only 27 to 39 percent by 2030, well below the 50 percent reductions they’re aiming for. Since then, more states have found themselves falling behind on their climate targets, including the two most populous — the Democratic strongholds of California and New York.

California is lagging on its goal of reducing carbon emissions 48 percent below 1990 levels by 2030, according to a June report. Meanwhile, New York state has yet to finalize a cap-and-invest strategy to hit its target of 100 percent carbon-free energy by 2040 and is off track to hit its utility-scale solar and wind targets, although it has achieved its goals for distributed and community solar projects.

For the energy transition to continue despite the headwinds of a second Trump administration, these two leading states — and the others that have enshrined decarbonization goals in law — need to do all they can to deliver on their climate commitments.

Should Trump gut the Inflation Reduction Act, the task at hand for these states will become more difficult. Some analysts doubt this will happen because the law has funneled billions into red states and thereby earned some Republican defenders.

The law’s litany of clean energy tax credits make solar, wind, and storage projects into no-brainers; they were already cost-competitive with fossil fuels before the subsidies. The EV incentives help bring the cost of electric models in line with gas cars. Its bevy of grant programs — from money for bolstering the grid to funding for home electrification and low-income solar — are helping states transition away from fossil fuels.

All of this makes it far cheaper and easier for states to achieve their clean energy targets and emissions-reduction goals.

It’s unclear which of the Biden administration’s climate accomplishments will remain intact — but what is clear is the ever more urgent need for states to push forward on their climate goals, however difficult that may become.