Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Insurers are in the business of risk. But some perils make them nervous. Attacks on computer networks are a prime example. Berkshire Hathaway’s Warren Buffett compares them to rat poison because of the spiralling impact on policies of a single event.

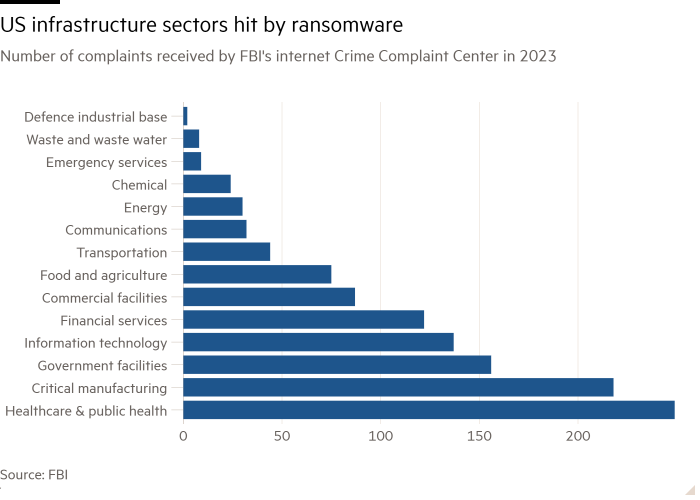

The escalating global cost of such crime — expected by US officials to exceed $23tn in 2027 — far outstrips the cyber insurance market, at roughly 800 times smaller. Insurers argue that such a vast gap can only be bridged by governments. The case is not clear cut.

Insurer Zurich and broker Marsh McLennan are the latest to advocate state intervention. They point to precedents provided by nuclear energy risks, natural disasters and terrorism. A government backstop might encourage insurers and reinsurers to extend coverage and offer extra capacity, says the Geneva Association, a global association of insurers. Such a move could improve resilience because insurers should require policyholders to install strong controls. That might create a virtuous cycle, reducing the chance the government is ever forced to step in.

But there could be unintended consequences. Knowing a government would foot the bill might encourage more attacks — especially state-sponsored ones. Another worry is that it could cramp the development of the fledgling but fast-growing cyber insurance market. A badly designed government backstop might impede innovations such as last year’s pioneering cyber catastrophe bond.

Defining the threshold that would trigger a government backstop is fraught. Cash-strapped governments could find themselves on the hook for more than they bargained for, some experts reckon. Patrick Tiernan, chief of markets at Lloyd’s of London, argues the insurance industry needs to do more modelling and client education before it can ask for government help. Citing intelligence sources, he suggests that roughly nine out of 10 cyber attacks could be prevented with better cyber hygiene.

Given the poor controls in many companies, a government backstop clearly creates moral hazard. It might well make companies less motivated to shore up their protections against cyber attacks. It is not clear why companies that do not employ basic cyber protections should be subsidised by taxpayers, says Daniel Woods, lecturer in cyber security at the University of Edinburgh.

There is a case for state intervention to bridge the gap created by the war and infrastructure exclusions in insurance policies. But governments are rightly reluctant to write blank cheques. As things stand, there is limited evidence that a broadly based backstop is needed. It would probably take a truly catastrophic cyber attack to change that view.