Sir Keir Starmer has promised that 2025 will be “a year of changing Britain for the better”.

After a rocky start to his government, the first six months of the new year will prove crucial, with a raft of pro-growth policy measures and a three-year Spending Review due to be completed by early summer.

Here is the progress so far — and what to watch for in the coming months.

Health and social care

Within weeks of entering government, ministers reached a deal with junior NHS doctors in England after offering a pay rise of 22 per cent over two years, ending a wave of strikes that had dragged on the health service for months.

The health service was also the big winner in the October Budget, enjoying a £22.6bn rise in its day-to-day spending allocation over two years and a £3.1bn increase in its capital allowance.

The day-to-day increase over two years represents an average real terms growth rate of 3.4 per cent in total Department of Health spending, and 4 per cent for NHS England.

That was the largest real-terms growth in day-to-day spending since 2010, outside the pandemic, but still below the long-run average of increases in health service spending going back to the 1950s, which have been between 3.6 per cent and 3.8 per cent.

Hospital bosses warned that the billions of pounds allocated was just enough to keep the show on the road. Experts also raised questions about the wisdom of pouring yet more money into a faltering system without a clear blueprint for change.

All eyes are now on the government’s 10-year health plan, which is expected in the spring.

Starmer’s top three priorities for reform include moving the NHS away “from an analogue to a digital” service, shifting more care from hospitals to communities, and being “much bolder in moving from sickness to prevention”.

Starmer has also pledged to meet a target that 92 per cent of patients should wait no longer than 18 weeks for elective treatment on the NHS by the end of the parliament. Commentators will be watching closely to see what progress is made and the impact focusing on this specific target will have on other areas of the health service.

Education and skills

Education was the other Whitehall department that did well in the Budget, with a £2.3bn (3.5 per cent) increase over the two-year period, including a £300mn increase for maintenance of dilapidated schools.

Ministers also agreed a 5.5 per cent pay deal with teachers; allowed universities a one-year increase in annual tuition fees in line with inflation; scrapped one-word judgments by schools inspectorate Ofsted and announced pilot breakfast clubs in primary schools; and launched a review of the schools curriculum.

The government then announced £740mn to start addressing the crisis in special needs education, with money to boost provision in mainstream schools to cut demand for places in more expensive special schools.

Now, businesses will be watching keenly to see if Skills England — a new body that is promised to yoke together the UK’s post-18 training landscape — lives up to its initial billing by the prime minister. Experts have warned that the early signs are not good.

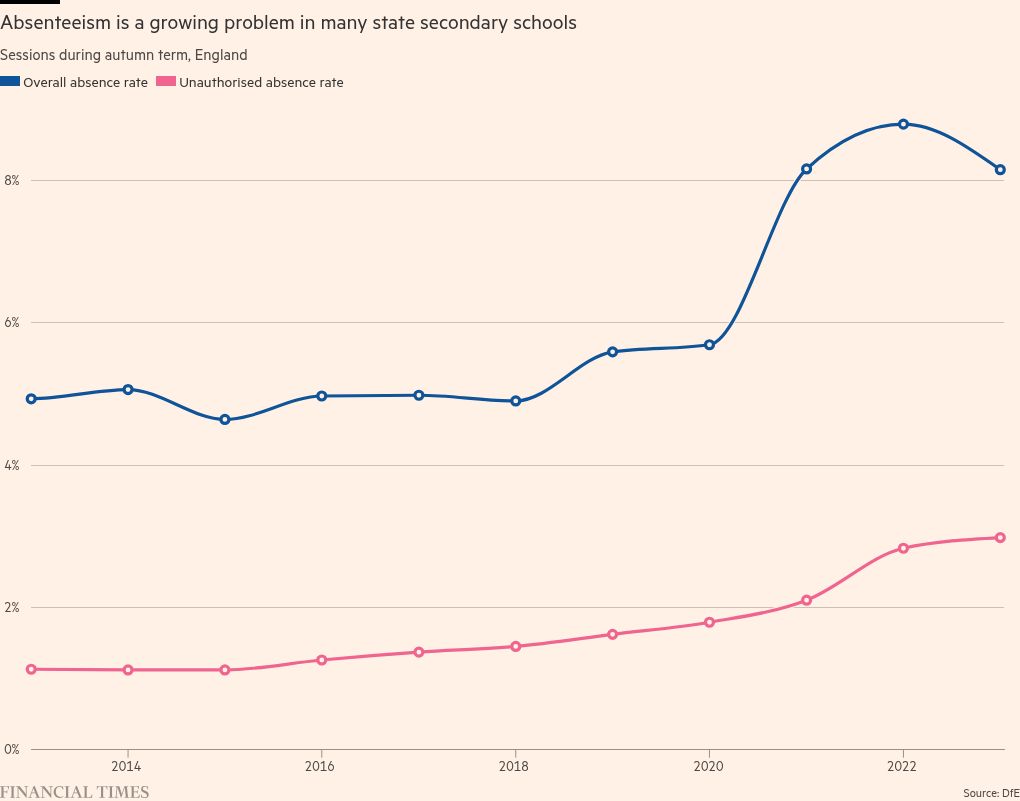

In schools, the government is focusing on boosting pupil attendance and teacher retention, but unions are spoiling for a fight over pay after the government recommended an increase of 2.8 per cent in 2025.

Education secretary Bridget Phillipson will also have to negotiate with the Treasury to allow universities to raise their fees by inflation every year, putting them on track to break the politically sensitive barrier of £10,000 a year by the end of the parliament.

Ministers are pledging to add 100,000 places to the Conservatives’ £4bn policy to provide parents of children from nine months to school age in England with 30 hours of free childcare a week, by September 2025. However, experts have warned that the sector will struggle to hire or retain the workers needed to create these new places.

Investment and trade

Labour staged a splashy investment summit for 200 chief executives in London’s Guildhall in October, at which Starmer promised to “rip up” bureaucracy that blocked investment and economic growth.

But the initial sheen of Labour’s business charm offensive fell away when the government slapped hefty tax rises on business in the Budget, leading CBI chief Rain Newton Smith to warn that industry was cutting back hiring and investment plans.

On the upside, the government published a green paper on its plans for an industrial strategy, appointing Microsoft UK chief executive Clare Barclay to head up a new advisory council that will act as the interface between government and business.

Whitehall officials said the upcoming white paper will look at the wider business environment, intersecting with the local growth plans being developed by mayors and councils to create clusters where the UK has a competitive advantage.

The Department for Business and Trade is expected to publish its plans for eight high-growth sectors, including life sciences and advanced manufacturing, identifying where the government will deliver what the green paper calls “temporary catalytic support” including cash investment, targeted interventions on skills, planning and deregulation.

Jordan Cummins, head of the competitiveness department at the CBI, said the industrial strategy had quickly become the biggest thing on the positive side of the ledger after a very tricky Budget. “Business will be watching closely to see how quickly the government can hit the ground on these new plans,” he added.

The UK will be balancing the trade-offs of its promised “reset” with the EU against the demands of an incoming Donald Trump administration in the US that has promised to impose potentially damaging 20 per cent tariffs on imports from China and Europe.

Devolution and local government

Starmer summoned England’s growing contingent of metro mayors to Downing Street within days of the general election, promising a major wave of devolution. A new white paper published just before Christmas provided more powers over planning, housing and transport, although some mayors have been frustrated that it was not more ambitious.

Mayors are now working on “growth plans” for their respective areas.

The most eye-catching proposal in the white paper was perhaps the plans to abolish district councils in the biggest local government reorganisation in 50 years — a move intended to make future devolution simpler.

Meanwhile, the sector remains in a precarious financial position. Although ministers have moved to try and clear a huge backlog of outstanding audits that has begun to have ramifications for Whitehall’s own accounts, the spectre of bankruptcy still hangs over councils struggling to balance their books.

The sector received an above-inflation funding increase in the Budget, but continues to struggle with severe demand for social care and homelessness services.

In the future, rows are expected over the local government reorganisation plans. There have already been warnings that it will lead to the creation of “mega councils” and undermine local democracy.

With only about half the population of England having a mayor, ministers also hope to sign further deals in order to fill the devolution landscape up with more elected figureheads as part of plans to drive economic growth.

They have also promised a three-year settlement for local government based on a “fairer” needs-based formula, to help councils financially stabilise and support some of the poorest areas.

But the sector was not singled out in the prime minister’s recent “milestones”, intended to focus Whitehall on his priorities. As a result, it may not be the beneficiary of much largesse at next summer’s spending review.

Planning reform and housebuilding

Labour has announced significant reforms to the sclerotic planning system as part of its pledge to “Get Britain building again” and hit its manifesto target of constructing 1.5mn homes during the parliament.

The reforms to the National Planning Policy Framework include imposing mandatory housebuilding targets on local councils, opening up ugly sections of the greenbelt — dubbed “grey belt” by ministers — and providing £100mn to help councils speed up planning decisions.

Starmer has admitted that 1.5mn homes is a “hugely ambitious” target given that the last time England succeeded in building 300,000 new homes in a single year was in 1969 — over half a century ago.

By midsummer the New Towns Taskforce will also identify the locations where the government should build a series of new towns and urban extensions.

The government will introduce a planning and infrastructure bill in 2025 that promises to create powers for central government to bypass local councils, using “targeted planning committees” to streamline development.

However, local authorities have warned that it will still take time for the effects of the reforms to feed through into higher housebuilding.

Richard Clewer, planning spokesperson for the County Councils Network, said more immediate results would come from policies to force developers with large existing planning permissions to “use them or lose them”.

“If we are serious as a country about building more houses, we can’t just want more planning permissions, we need to build out the ones we have already given,” he added.

One Whitehall official also said the Spending Review would be critical: “We’ve built 200,000 homes a year, on average, over the last 40 years because that’s what the market delivers. If the government wants to buck that trend then the state will have to invest to create the additional demand.”