Archaeologists have discovered the site of the long-lost palace of England’s last Anglo-Saxon king.

Using a combination of ground-penetrating radar, data from past archaeological excavations (including a medieval loo) and information from an 11th century artwork, investigators from two UK universities have succeeded in locating the political headquarters of King Harold ii, the English monarch who was defeated and brutally killed at the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

The archaeological investigations – carried out in and around the village of Bosham, near Chichester, West Sussex – has revealed that Harold’s royal palace complex covered around an acre and consisted of several buildings including a large timber hall. Located next to a harbour and a church, it was surrounded by a 250 metre long 3 metre wide moat.

But the new research also has potential implications for understanding where Harold may have been buried.

He is the only English monarch whose final resting place is uncertain.

Traditionally, he is often said to have been buried at Waltham Abbey in Essex.

But some medieval sources provide information that would be more consistent with him having been buried adjacent to his palace. Indeed, in 1954, the remains of a high-status Anglo-Saxon man were found under Bosham church – but have never been scientifically tested, despite several aspects of the Individual being consistent with what is known about Harold and his death.

The village of Bosham:

The palace complex has been identified through multiple strands of evidence.

Firstly, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle indicates that Harold’s palace was located in or near Bosham.

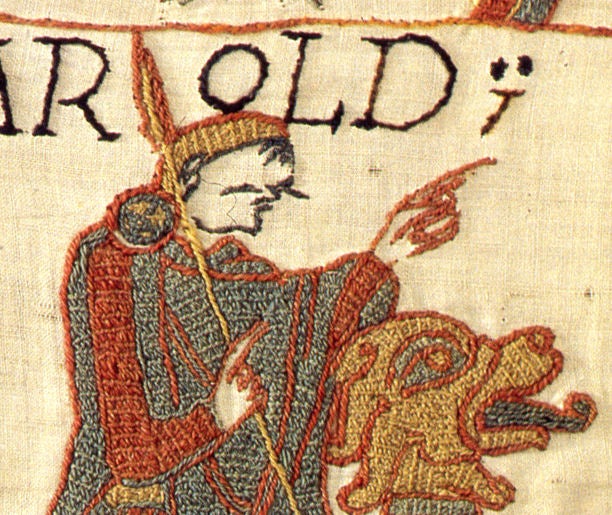

Secondly, the Bayeux Tapestry – the 11th century embroidered pictorial account of the Norman conquest – shows Harold approaching a very high-status building in Bosham.

But those medieval sources do not show precisely where the palace was in the Bosham area.

However, a recent re-analysis, by archaeologists from the universities of Newcastle and Exeter, of archaeological data from Bosham, have managed to pinpoint the exact location of the palace – by identifying clues indicating a very high-status Anglo-Saxon building – clues which include a substantial moat, evidence for a large tiled building (as illustrated in the Bayeux tapestry) and an internal en-suite loo, a feature in the Anglo-Saxon era normally only associated with very high status buildings.

Although Harold is famous for being England’s last Anglo-Saxon king, he only reigned for just over nine months.

His defeat and death at the Battle of Hastings was arguably the single most significant event in English history – because it totally and permanently changed the political, cultural, legal, social and linguistic nature of England and ultimately of Britain and much of the wider world.

However Harold’s violent demise was part of a wider phenomenon of endemic political and military violence throughout medieval Europe. Indeed the 1060s – the decade in which the Battle of Hastings was fought – saw literally dozens of wars raging in virtually every part of Europe including France, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Hungary and of course England.

What’s more, the defeat of Anglo-Saxon England in 1066 was part of a complex international geopolitical series of conflicts. William was supported by the vast German empire (also known as the Holy Roman Empire), the Kingdom of France and the Papacy.

Harold was just supported (perhaps even militarily) by Denmark – and perhaps politicly by Ireland.

The geopolitical situation was further complicated by there having been no less than four claimants to the English throne in 1066 – William, Duke of Normandy (who won the Battle of Hastings), the Norwegian king (Harald Hardrada); Edgar, an Anglo-Saxon teenage prince who was the grandson of an English king who had died half a century earlier); and of course Harold (who had no royal blood but had been elected as king of England by the English ‘Witan’ – a sort of national parliament).

The new research, published this month in The Antiquaries Journal, was led by Dr Duncan Wright, Senior Lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at Newcastle University in association with Professor Oliver Creighton of the University of Exeter.

The original excavation at Bosham, which has provided much of the key evidence for the search for Harold’s palace, was carried out by West Sussex Archaeology.

“Looking at all the evidence, it is beyond reasonable doubt that we have now identified the location of King Harold’s main power centre, the one famously depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry,” said Dr Wright.

The research at Bosham was carried out as part of an important wider Newcastle University and the University of Exeter research programme, the Where Power Lies project, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. The project aims to explore the origins and early development of aristocratic centres like Bosham, assessing for the first time the archaeological evidence for such sites throughout England.