Archaeologists are beginning to reveal the secrets of a vanished prehistoric land which now lies at the bottom of the North Sea.

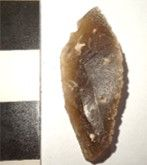

Using special dredges, scientists have just brought to the surface 100 flint artefacts made by Stone Age humans between 15,000 and 8,000 years ago.

The artefacts – a number of small flint cutting tools, as well as dozens of flint flakes from tool-manufacturing activity – were recovered from the seabed in three different locations on the southern coast of the prehistoric drowned land.

Each newly discovered ancient site, some 20 metres below the stormy surface of the North Sea, is located next to a series of long-vanished estuaries.

The sites – 12 to 15 miles off the Norfolk coast – are expected to yield hundreds more artefacts which will begin to reveal how the people of the lost land lived.

It is thought their economy revolved around hunting red deer and wild boar and harvesting shellfish. Parts of the bottom of the North Sea are of huge archaeological importance because they have been relatively untouched by humans since they were inundated between 10,000 and 7,500 years ago.

On land, Neolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age, Roman, medieval and modern settlements, roads, forestry activity and agriculture have destroyed huge quantities of early human archaeology.

In Britain 99 per cent of the period of human occupation predates Neolithic and later settlement and agriculture. That 99 per cent has been partly obliterated by the more recent 1 per cent of human prehistory and history.

But at the bottom of the North Sea, post-Stone-Age human impact is much reduced, and as a result some Stone Age hunter-gatherer “landscapes” have survived largely intact on the seabed.

“Our investigations at the bottom of the North Sea have the potential to transform our understanding of Stone Age culture in and around what is now Britain and the near continent,” said the North Sea archaeological investigation’s leader, Professor Vince Gaffney of the University of Bradford’s Submerged Landscapes Centre.

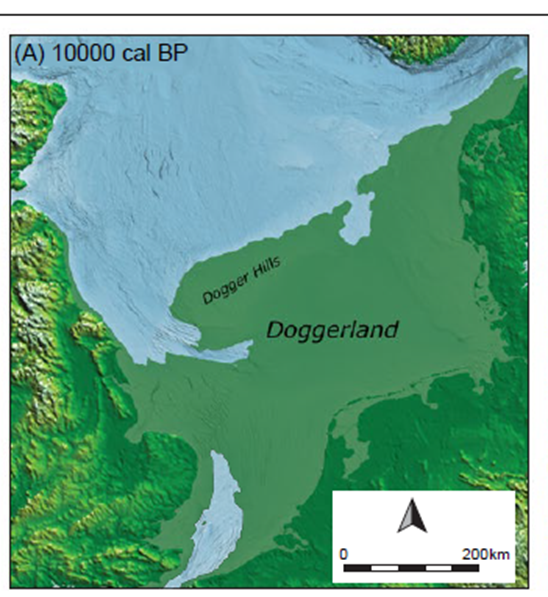

This prehistoric treasure chest hides a tragic story, and a warning. Over a period of just 1,500 years (roughly 8000BC to 6500BC), an area almost the size of Britain was swallowed up by the sea as a result of a rise in sea levels caused by an intense period of global warming.

In 8000BC, around 80,000 square miles of what is now the southern part of the North Sea was dry land. But by 6500BC, only around 5,000 square miles were left.

During that period, an average of 50 square miles of land were lost every year – sometimes much more. As sea levels rose, the Stone Age population, who lived mainly by the coast and thus at elevations ever-closer to sea level, became increasingly vulnerable to seasonal flooding.

As hunting grounds were swallowed up by the sea, successive generations of the area’s inhabitants must have been driven from their traditional lands.

Future archaeological work is likely to shed light on how that drama unfolded. However, what happened to Britain’s lost prehistoric North Sea world is a clear warning to 21st-century humans as to what modern global warming will do to many coastal and lowland communities worldwide over the coming decades and centuries.

The continuing archaeological investigation in the North Sea is a joint operation run by the University of Bradford and Belgium’s Flemish Marine Institute. The exploration is being undertaken in collaboration with the North Sea’s wind farm projects and Historic England’s Marine Planning Department.

The drowning of so much Stone Age land by post-Ice Age sea-level rise was a pivotal event in British prehistory – and Britain’s status as an island dates from that time. Scientists involved in the research believe that as well as helping us to understand the past, their work can also be a warning for the future.

“As we delve into the past, we are beginning to appreciate ever more clearly what future sea-level rise could do to humanity. Our collaboration with the North Sea wind farms community is part of Britain’s efforts to reach net zero and to thereby combat global warming,” said Professor Gaffney.