Adam Rowlands’ boots scrunch through the pebbles as he describes the abundance of wildlife in the wetlands behind the beach in the Suffolk town of Aldeburgh.

“We have scarce white-fronted geese, alongside important numbers of pintails, wigeons, and other waterfowl,” reels off Rowlands, an area manager for the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, a UK charity. “In the breeding season there are lapwings and redshank, and further inland in the heathland there are nightjars and woodlarks and nightingales.”

Standing near a steel sculpture of a giant scallop, he gestures north towards the seaside village of Thorpeness and the Sizewell B nuclear power plant beyond. To his chagrin, this strip of coast beloved by nature enthusiasts has been earmarked for an array of new electricity infrastructure to help Britain’s energy supply go green.

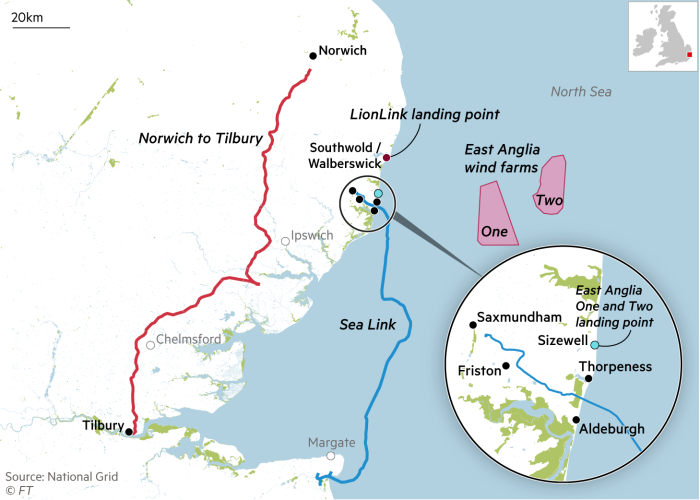

Scottish Power wants to bring cables onshore from two vast new wind farms in the shallow waters of Doggerland, in the North Sea. National Grid has proposed a 138-kilometre offshore electricity link between Suffolk and Kent called Sea Link, and another to the Netherlands, known as LionLink, to help the two countries manage surges in demand.

But in September, more than 400 people gathered to protest against the plans. For the RSPB, in particular, the biggest concern is Sea Link. The charity argues that tunnelling beneath the wetlands will have a detrimental effect on wading birds, which are susceptible to habitat disturbance.

“We see the need for net zero . . . and the renewable transition. But we believe there are routes that can avoid going through this site,” says Rowlands. “It feels like we are addressing climate change at the expense of the biodiversity crisis, which could be avoided by better strategic planning.”

This argument is part of a broader debate playing out across the country. Wind farms around Britain’s coastline are central to the Labour government’s plans to achieve climate targets, including decarbonising the UK’s electricity system by 2030, and increase energy self-sufficiency. Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer is taking a firm hand, vowing to “rip up the bureaucracy that blocks investment” into renewable energy projects and turn the UK into a “clean energy superpower”.

Tough decisions now, according to Starmer’s rhetoric, are worth it to bring down bills and give Britain greater energy security. But his bullish approach is putting him at odds with the determined local groups.

The stand-off is a key test of whether Labour can keep communities onside as it pushes ahead with its green transformation of the UK’s economy — a gamble that will be watched around the world.

Opposition is mobilising. In Aldeburgh, protesters from Suffolk Energy Action Solutions (SEAS) have the support of many local residents, including Andrew Heald, founder of Fishers Gin, an upmarket distillery. “This is potentially catastrophic for the local economy,” he says over sandwiches at a seafront hotel. “We rely on nature and biodiversity, which are in direct conflict with infrastructure projects.”

Others are unhappy about plans for new substations that would be built on the edge of Friston, a medieval village about 6km inland from Aldeburgh, and converter stations just outside nearby Saxmundham.

The converter stations needed for Sea Link and LionLink would be huge — roughly the size of Buckingham Palace, according to Robert Nichol, the arable farmer who owns the land in question (the stations’ proposed sizes have been confirmed by National Grid). “My father came here in 1955 with his young wife, we were all brought up on the farm. I’ve been farming it since 1997, growing wheat, barley, milling wheat, soft wheat and beans,” he says.

National Grid wants to buy 185 acres from his 345-acre farm using compulsory purchase orders and would pay compensation — but Nichol says this would leave the business “unviable”.

“I’ve got a son and two daughters and I wanted [the farm] to go to one of them. What will be left to pass on to whichever of them wants to be a farmer? It will see the heart ripped out of this place.”

It was in the 1950s and 1960s that pylons, the steel towers that support the cables that transmit electricity, were erected in large numbers to keep up with postwar energy demand. “Bestride your hills with pylons/ O age without a soul,” lamented English poet John Betjeman in his work at the time.

Now the UK’s green fields face fresh upheaval. Previous Conservative and coalition governments helped the UK develop an offshore wind market, which is second only to China’s, and become the first G7 country to stop using coal to generate electricity.

Britain generates just under a third of its electricity from wind turbines, concentrated on the Scottish coastline or in the Highlands. Now ministers want to go further and make offshore wind the backbone of the country’s clean electricity system.

To achieve this, the existing electricity grid, built for the fossil fuel era, will need updating. Transporting electricity from renewables projects to the areas where it is needed will require about 1,000km of new power lines and 4,500km of undersea cables. That also includes 520 pylons, each 50 metres high, running in a 180km line from Norwich, in Norfolk, to Tilbury, Essex.

Rosie Pearson, a member of the Essex Suffolk Norfolk Pylons Action Group, says the group supports offshore wind in principle. But their concern is that “visually intrusive and ugly” pylons would damage a beautiful vista once painted by landscape masters Gainsborough and Constable.

“Because it is flat, these pylons, each as tall as Nelson’s column, will destroy everything people like about the area,” she adds. Pylons are also an ecological nightmare, Pearson says, referring to one incident in Kent where over 170 swans died after flying into power lines.

But neither National Grid nor the government want to change gear. The National Energy System Operator concluded in a report in November that the 2030 clean power goal is doable, provided that “several elements . . . deliver at the limit of what is feasible”. This included about £40bn of annual investment, the operator added.

To meet the need for up to 35GW of new offshore wind, 13GW of onshore wind and 30GW of solar — all of which needs connecting to the grid — “twice as much [transmission] network needs to be built in the next five years as was built in total over the past decade”, the operator said.

But projects are frequently delayed, held back by lengthy planning timelines and vigorous community objections. In a decision that sent shudders through the industry, in 2021 the High Court quashed planning permission for Swedish developer Vattenfall’s giant wind farm off the Norfolk coast after a local resident raised concerns about the impact of cables taking the power into land.

The project was awarded permission again in 2022 by Kwasi Kwarteng, the minister then in charge of UK energy. At the end of 2023, it was sold to German utility RWE, which has yet to begin construction.

Labour is selling its ambitions for clean power by 2030 and other green policies as a win-win situation. As well as the climate imperative, it argues that renewables will create new jobs and reduce energy bills.

How many green jobs can be created from the renewables boom — and the extent to which they will be in the same locations as old industrial jobs that will have been lost — is yet to be answered. There are also question marks over whether there will be enough trained workers.

National Grid says the energy sector will need to fill about 400,000 jobs up until 2050 to meet the broader net zero goal. The Offshore Wind Industry Council, a trade group, has predicted that developing 50GW of offshore wind by 2030 would require 100,000 roles.

“Wherever I go across the UK, people are talking about skills shortages,” says Carl Sizer, chief markets officer at the UK arm of consultancy PwC.

The jury is also out on the issue of smaller bills. Analysis by the National Energy System Operator, published in November, found that the overall costs of a clean power system in 2030 would be no more than the status quo. But it could not predict how this would feed through into consumer bills.

It cautioned that costs “could escalate” if supply chains are stretched in the race to hit the target. Much will also depend on how the government funds subsidies and whether its assumptions on gas prices prove accurate.

Ministers also face a fraught decision over whether to move to “zonal” pricing, a system whereby electricity prices differ by region according to how much power is being produced locally. This could mean, for example, hours of the day when people in Scotland are able to buy electricity very cheaply due to high winds nearby, while people in London may be paying a higher price.

The government said in December it would ensure communities “directly benefit from hosting clean energy infrastructure” — but details remain scant. Many companies already pay into local community funds in areas that have agreed to accept electricity equipment, but this is not mandatory.

“We are sympathetic to the fact that communities are being asked to host infrastructure, quite often for the first time,” says John Pettigrew, chief executive of National Grid.

“Our job is to bring the electricity from where it’s produced to where it’s consumed. We work really hard to listen to communities,” he adds. “Ultimately, if people aren’t comfortable with a secretary of state’s decision, they have the right to go to judicial review on that.”

Adam Berman, head of policy at trade body Energy UK, says that the infrastructure needed for the “transformation” of the energy system would inevitably lead to some “disruption” for communities. There will always be some “loud voices” opposing projects, he adds, despite such infrastructure being in the national interest.

“You need to make sure that where infrastructure is built it’s done in the least disruptive, most environmentally friendly and lowest cost way,” he says.

Keith Anderson, chief executive of Scottish Power, says the energy company can move “at a hell of a speed” to deliver projects once it gets the all clear. But he says legal challenges and protests may end up delaying the government’s 2030 target.

“If you can’t find a way of timelining it and managing it as a parallel process and all the interfaces incredibly carefully, you will never deliver clean power by 2030,” he adds. “It will just take too long to get it through the system.”

Those working closely with Starmer say he takes a “macho” approach to building new clean energy infrastructure — and 1.5mn new homes — because they can be lasting proof that he can get things done. “He’s not afraid of upsetting people over this,” says one colleague.

But some new Labour MPs in rural constituencies previously held by the Conservatives are concerned that their chances of re-election will be jeopardised by Starmer’s uncompromising approach to development, exacerbated by recent changes to the inheritance tax treatment of agricultural estates.

Kemi Badenoch, the Conservative leader, has sought to exploit the issue, criticising the government for imposing “massive solar farms” and a “complex web of pylons and cables across the countryside”.

Pearson, from the anti-pylon group in East Anglia, says the prime minister has been “incredibly patronising”.

“It’s ignorant to ignore the evidence that there are far better ways of doing this,” she says. “It’s going to be extremely damaging, the way Labour talks to communities with concerns . . . it entrenches people in their battle lines.”

National Grid says that when it builds new overhead lines “we always try to avoid communities and individual properties as much as possible” and that it understands the visual impact can be a concern for some local people.

But that cuts little ice with Fiona Gilmore, the volunteer leader of SEAS, whose backers include locally-born Hollywood actor Ralph Fiennes.

As she walks through Friston’s fields, Gilmore says her group is in favour of offshore wind farms. But they believe the energy they generate should be pooled at sea and transmitted to shore along shared cable lines — of the kind used by Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany and Denmark — rather than being “dumped at the nearest convenient site”.

SEAS has commissioned a report suggesting the work will cost local tourism £1bn over a decade, equivalent to a 15 per cent drop. “Tourism is the biggest industry here. Once restaurants or hotels close, they won’t come back,” she says.

National Grid says it will deliver Sea Link through the RSBP’s North Warren reserve using “trenchless underground construction methods” that minimise the impact on wildlife, traffic and local communities. The company says it “does not recognise” the £1bn figure of potential damage to tourism.

The company says that putting cables underground would cost bill payers “as much as five to 10 times more than they’ll pay for overhead lines”, adding: “Even offshore infrastructure has to come onshore somewhere.”

Instead, it will seek to blend its converter station near Saxmundham into the local scenery with “exterior planting and green roofs”.

Anderson, from Scottish Power, says underground cables bring their own environmental challenges, noting that there was a debate several years ago about how some of the new electricity infrastructure should be built.

“The UK decided to go down a point-to-point route . . . could you change that? The issue would be the same — time, speed and cost,” he says.

Gilmore is far from convinced, saying the big energy companies “don’t seem to have thought about the impact on the countryside or the environment” and has previously threatened to take the developers to judicial review “again and again and again”.

But Starmer’s administration has revealed that it is now exploring overhauling planning rules so that claimants can only apply once for judicial reviews of large infrastructure projects. SEAS has already lost two legal cases and Gilmore admits that raising funds can be “really difficult”.

“There are lots of middle class affluent people living here, but they are exhausted and drained because this has been going on for years,” she says. For residents like her, who have to live alongside these developments, it feels like “rural communities are doomed to a nightmare situation”.

Cartography and data visualisation by Steven Bernard

This article has been amended since original publication to correct that National Grid is interested in buying the farmland owned by Robert Nichol