Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

CNN

—

As a piece of spaceborne garbage veered toward the International Space Station in November, the seven astronauts on board braced themselves.

A Russian spacecraft attached to the space station lit its engines for five minutes, slightly tweaking the station’s trajectory and moving the football field-size laboratory out of harm’s way. If the space station had not changed course, the debris could have passed within 2 ½ miles (4 kilometers) of its orbital path, according to NASA.

Debris striking the space station could have spelled disaster. An impact might have depressurized segments of the station and left the astronauts scrambling to return home.

What’s more concerning: The potential strike was not all that rare of an occurrence. The International Space Station has had to make similar maneuvers dozens of times since it was first occupied in November 2000, and collision risks are growing every year as the number of objects in orbit around Earth proliferate.

For years, space traffic experts have raised alarm bells about the increasing congestion. Earlier collisions, explosions and weapons tests have resulted in tens of thousands of pieces of debris that experts are tracking and possibly millions more that cannot be seen with current technology.

And while risks to astronauts may be a top concern, congestion in orbit is also hazardous to satellites and space-based technologies that power our everyday lives — including GPS tools as well as some broadband, high-speed internet and television services.

“The number of objects in space that we have launched in the last four years has increased exponentially,” said Dr. Vishnu Reddy, a professor of planetary sciences at the University of Arizona in Tucson. “So we are heading towards the situation that we are always dreading.”

The event Reddy referred to is a hypothetical phenomenon called Kessler Syndrome.

Named for American astrophysicist Donald Kessler and based on his 1978 academic paper, Kessler Syndrome — as the term is used today — has a muddy definition.

But the phrase broadly describes a scenario in which debris in space sets off a chain reaction: One explosion sends out a plume of fragments that in turn smash into other spaceborne objects, creating more detritus. The cascading effect may continue until Earth’s orbit is so clogged with junk that satellites become inoperable and space exploration must come to a grinding halt.

Researchers disagree about the current level of risk and when, exactly, congestion in space may reach the point of no return.

But there is widespread consensus about one thing: Traffic in space is a serious problem in desperate need of addressing, according to CNN interviews with scientists and space traffic experts.

Since the dawn of spaceflight in 1957, there have been more than 650 “break-ups, explosions, collisions, or anomalous events resulting in fragmentation,” according to the European Space Agency.

Those incidents have included satellites that have accidentally collided with each other, rocket parts and spacecraft that have unexpectedly exploded, and weapons tests from nations including the United States, Russia, India and China that have spewed detritus across various altitudes in orbit.

Russia, for example, launched a missile at one of its own satellites as part of a weapons test in 2021, creating more than 1,500 traceable pieces of debris.

The last major accidental collision between two spaceborne objects occurred in February 2009 when a dead Russian military satellite, called Kosmos 2251, rammed into Iridium 33, an active communications satellite operated by US-based telecommunications firm Iridium. That event produced a massive cloud of nearly 2,000 pieces of debris that were nearly 4 inches (10 centimeters) in diameter and thousands of even smaller pieces.

Similar events on a smaller scale are also common: a US Air Force weather satellite, for example, broke apart in orbit on December 19, creating at least 50 new pieces of debris, LeoLabs, a company that tracks objects in space, said on Monday. It was only the latest in a string of four “fragmentation” events over the past few months that created more than 300 new pieces of litter.

What we can and can’t see

For those managing satellites, congestion in space can be a nightmare. It’s common for a satellite operator to receive a dozen or more alerts per day about potential collisions.

The process of tracking objects in orbit — called space situational awareness — involves tracing possible “conjunctions,” or close approaches between two entities.

In one incident this year, for example, a NASA weather satellite narrowly missed colliding with a defunct Russian rocket by less than 65 feet (20 meters), according to LeoLabs.

But the risks may be even higher than what space situational awareness can predict.

For the most part, an object must be larger than a tennis ball to be tracked. The remaining objects are too small to reflect light or in distant areas of orbit that are difficult to observe directly.

“Even with today’s best sensors, there are limits to what can be reliably ‘seen’ or tracked, and smaller space debris is often untrackable,” said Bob Hall, director of special projects at COMSPOC Corp., a space traffic software company.

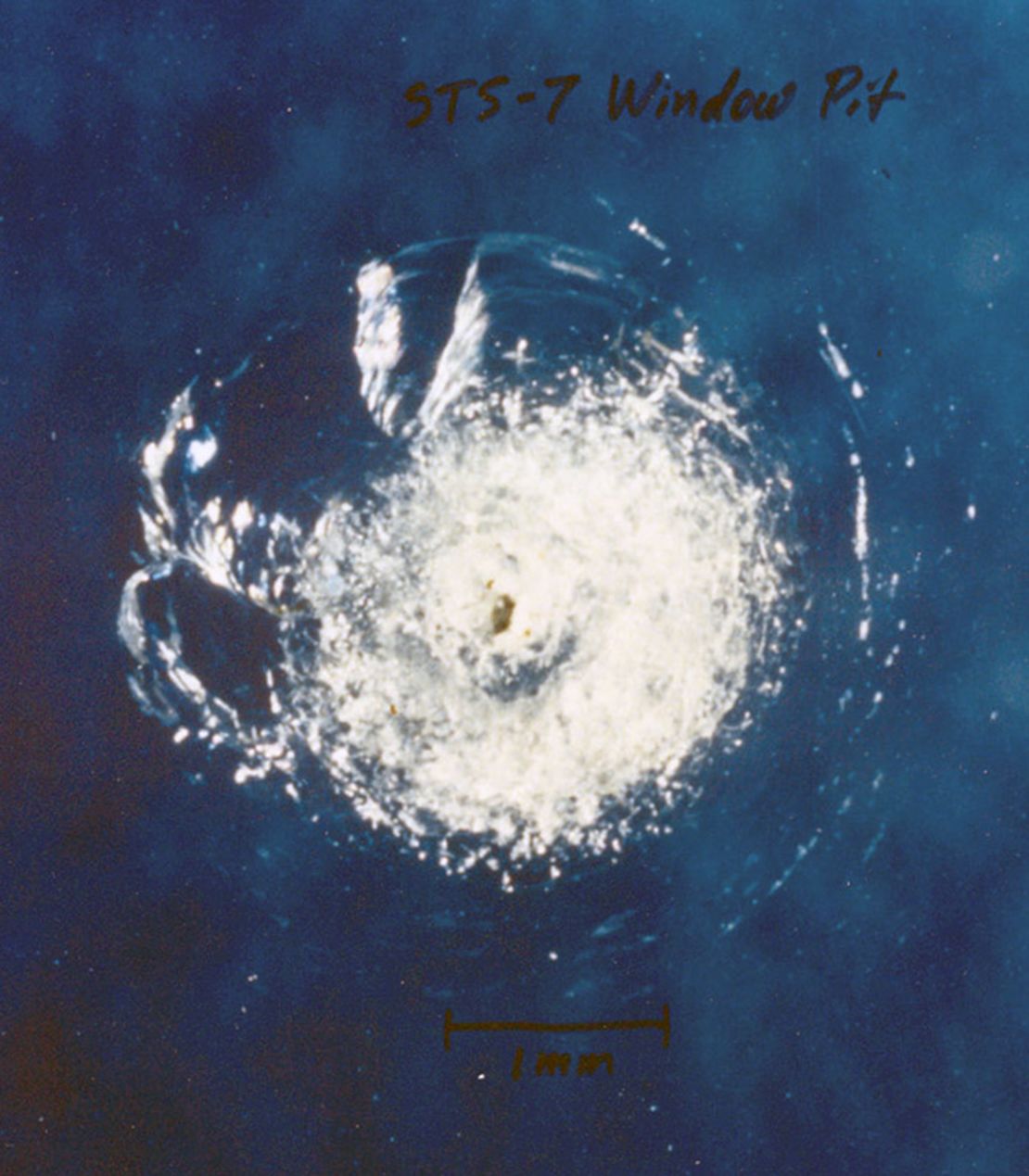

But small objects can still pose significant threats. In orbit, objects whirl around so fast that even a fleck of paint is capable of smashing through metal, according to NASA. That means any piece of junk left in space is deeply concerning — and potentially catastrophic.

Exactly how a chain reaction of collisions in space might play out is not clear.

Different regions of Earth’s orbit have their own levels of congestion and risk. Low-Earth orbit, which extends to around 1,200 miles (2,000 kilometers ) above the planet’s surface, is by far the most crowded.

This area is home to two crewed space stations and massive constellations of satellites that beam internet — such as SpaceX’s network of nearly 7,000 Starlink satellites — monitor weather, observe crop production or analyze the climate.

If a ripple of explosions happened in low-Earth orbit, it could threaten astronauts’ lives, halt rocket launches and lead to the destruction of all the satellite technology present there.

The good news in this scenario, if there is any, is that disastrous conditions may not last for generations to come: “We still have remnants of atmosphere in the low-Earth orbit, so we have a natural cleaning mechanism,” said Carolin Frueh, an associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at Purdue University in Indiana.

At an altitude of around 300 miles (500 kilometers), objects in orbit will naturally fall back to Earth or disintegrate in the atmosphere within about 25 years, Frueh said, indicating that a debris field at this distance likely would not threaten access to space for generations to come.

But the picture changes rapidly at higher orbits. At nearly 500 miles (800 kilometers), it would take at least a century for a piece of debris to be naturally dragged out of space. At more than 621 miles (1,000 kilometers), the process would take thousands of years.

That’s bad news for geosynchronous orbit — a region about 22,236 miles (35,786 kilometers) from Earth’s surface — which is home to quarter-billion-dollar communications satellites that beam TV and other services to broad swaths of the globe.

“The most dangerous place where this (Kessler Syndrome-like event) could happen is in GEO,” said Reddy, the University of Arizona researcher. “Because we have no way of cleaning it up in a quick way.”

The 2013 movie “Gravity” brought the idea of Kessler Syndrome to the big screen: A Russian missile strike on a dead satellite initiates a cascade of collisions, generating a cloud of junk that devastates other satellites and spacecraft.

But while the drama in “Gravity” unfolded over an hour and a half, a real-life Kessler Syndrome scenario would likely take years — or decades — to play out, experts said.

And since the film’s release more than a decade ago, congestion in orbit has rapidly increased: The US military was tracking about 23,000 objects then compared with 47,000 objects today.

Though there are ongoing efforts to calculate where, when and how a ripple effect might kick off, it’s an impossible task, Purdue’s Frueh said.

“As soon as we’re predicting into the future, we have to make assumptions,” Frueh said. “Every model is wrong — (but) some are useful.”

Models are inaccurate because even experts do not have a pristine picture of where objects are in orbit. Objects smaller than about 4 inches (10 centimeters) are largely invisible. What’s more, space weather can change orbital trajectories — so it’s difficult to predict exactly how and where debris is traveling, according to Dr. Thomas Berger, director of the University of Colorado’s Space Weather Technology, Research, and Education Center. Berger spoke on the topic on December 11 at the American Geophysical Union’s annual meeting in Washington, DC.

The size and shape of spaceborne garbage pieces are also a mystery. So, to model a single Kessler Syndrome effect, analysts would have to guess exactly how a satellite would break apart, how each piece of that debris would look, where it would travel and what other object it might hit next.

“What keeps me up,” said Dan Oltrogge, chief scientist and director of COMSPOC Corp.’s Center for Space Standards and Innovation, “is that the data is not accurate enough to allow you to actually avoid the thing you think you’re avoiding.”

Given that “Kessler Syndrome” is not an instantaneous event, scientists are debating whether the phenomenon could already be in motion. Kessler’s thought experiment asks researchers to consider whether — even if all rocket launches ceased — collisions in space would still escalate the number of objects in orbit. And it’s not clear if that point has been reached.

The researchers interviewed for this story offered differing perspectives on whether events indicative of Kessler Syndrome had already kicked off.

But Frueh said that’s why she no longer believes Kessler Syndrome is a useful term.

“I think it’s confusing for the public that different entities do not agree,” she said. “The concept itself is just not as clean and crisp as you would think.”

What experts do seem to agree on is that the situation in orbit is problematic. None said that they believed disaster could certainly be avoided. More likely, they said, the garbage in orbit will continue to proliferate.

Frueh said, “I’m pessimistic … that we will act timely enough to not have economic damage in the process.”

Dr. Nilton Renno, a professor of climate and space sciences and engineering at the University of Michigan, said that he is optimistic by nature. But the situation in Earth orbit reminds him of the ecological woes underway here on our home planet.

“The analogy that I like to think about space debris is plastic in the oceans,” he said. “We used to think that the oceans are infinite, and we throw in trash and plastic, and now we realize — no, those are finite resources. And we are causing huge damage if we are not careful about what we do.”

There are two big considerations when talking about preventing the proliferation of debris in Earth’s orbit.

One is cleanup technology: Companies and government initiatives are seeking to develop ways to drag debris out of orbit, such as the Drag Augmentation Deorbiting Subsystem, or ADEO, developed by the European Space Agency and tech company High Performance Space Structure Systems, or HPS GmbH. The prototype braking sail was successfully deployed from the ION satellite in December 2022, according to ESA.

The sail technology “provides a passive method of deorbiting by increasing the atmospheric surface drag effect,” an ESA release said, with the aim of causing a defunct satellite to descend more quickly and burn up in Earth’s atmosphere debris-free.

These methods, however, are experimental and exceedingly expensive, Renno noted. And it’s not clear who would be willing to pay for them.

The second consideration is regulation. Space policy experts have for years traced efforts to adopt new international guidelines or national laws aimed at preventing space companies or bad actors from acting irresponsibly.

There are some efforts in the works. In September, the United Nations adopted the Pact for the Future.

The document, adopted by member states, includes an intention for nations to “discuss the establishment of new frameworks for space traffic, space debris and space resources through the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space.”

The language appears nebulous, and space policy experts point out that the United Nations has no means of enforcement.

Perhaps more practical, Renno said, is for individual nations to adopt laws for space stakeholders. And he believes the United States should take a leadership role in that process.

The University of Arizona’s Reddy agreed.

“I think the biggest concern is the lack of regulation,” he said. “I think having some norms and guidelines that (are) put forward by the industry will help a lot.”